For decades, the “digital divide” has been a focal point in discussions about technological equity. Traditionally, this divide has been understood as a gap between those with ready access to computers and the internet and those without. Common wisdom has held that this divide largely falls along predictable lines: urban vs. rural, rich vs. poor, young vs. old, and white vs. minority populations. However, a groundbreaking study published in Telecommunications Policy challenges some of these long-held assumptions, particularly when it comes to internet speeds and racial demographics.

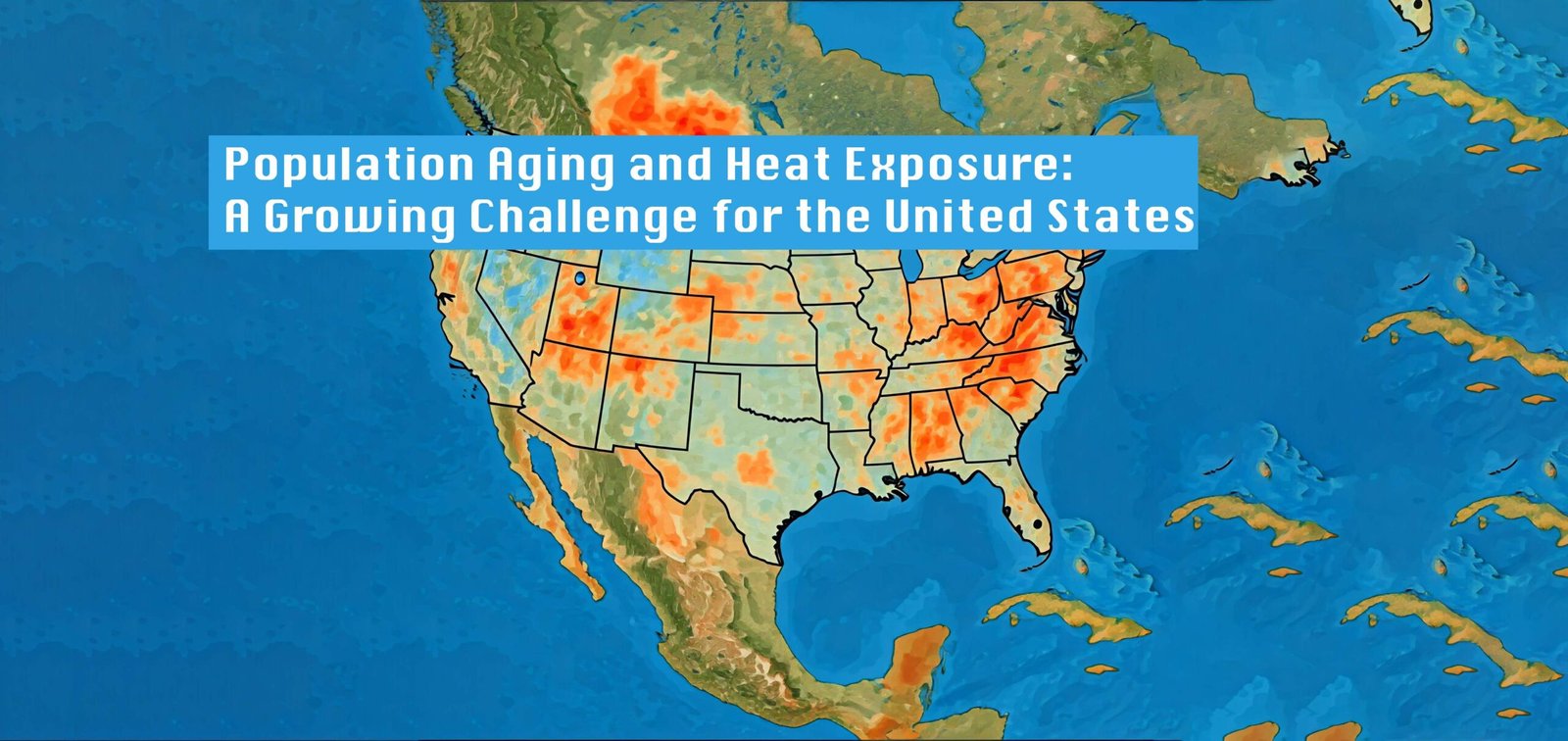

Researchers have conducted an extensive analysis of internet speeds across the continental United States, using data from over 80 million speed tests conducted by Ookla in 2021. Their study, which covered 97.8% of all census tracts, aimed to determine whether the usual disparities in broadband adoption persisted when examining actual internet performance.

Some findings aligned with expectations. Rural areas, for instance, were associated with significantly slower download speeds. The data showed that a 1% increase in rural population corresponded to a decrease of about 0.4 Mbps in download speed. Similarly, areas with higher poverty rates and older populations also experienced slower speeds. For every 1% increase in the population aged 65 or older, download speeds decreased by approximately 0.3 Mbps.

However, the study’s most surprising and potentially consequential finding relates to race and ethnicity. Contrary to conventional wisdom and previous studies on broadband adoption, areas with higher percentages of white, non-Hispanic residents were associated with slower internet speeds. This held true even after controlling for factors like rurality, poverty, and education levels.

The magnitude of this unexpected divide is noteworthy. The researchers found that, all else being equal, a census tract with 90% minority population would have an average download speed of 181 Mbps, compared to 171 Mbps in a tract with only 10% minorities. This 10 Mbps difference is roughly equivalent to the impact of shifting from a tract where 40% of the population is over 65 to one where only 10% are in that age group.

This pattern persisted across different racial and ethnic groups. For every 1% increase in Black, non-Hispanic population, download speeds increased by about 0.1 Mbps. Hispanic populations showed a similar, though slightly smaller, positive association with download speeds.

The reasons behind this unexpected trend are not yet clear. The researchers posit several potential explanations:

- Minority groups may be using more applications that require higher speeds, such as telehealth, video uploads, gaming, or working from home.

- There could be differences in household sizes or the number of devices per household across racial groups.

- White households may be more likely to opt for lower-speed, lower-cost plans when given the choice.

- There might be a growing distrust of the internet among some white conservatives, leading to less demand for high-speed services.

These findings have significant implications for policy and digital equity efforts. Many current initiatives, including the Digital Equity Act, explicitly target racial and ethnic minorities as underserved populations. While these groups may indeed lag in overall broadband adoption rates, this research suggests that those who do adopt broadband are using it at higher speeds than their white counterparts.

Studies also highlight the importance of looking beyond simple binary measures of internet access. As our digital economy evolves, the quality and speed of internet connections become increasingly crucial. A household with a slow, unreliable connection may struggle to fully participate in online education, remote work, or tele-health services, even if they technically “have internet.”

It’s worth noting that this study focused on fixed broadband connections and doesn’t account for mobile internet use, which could potentially show different patterns. Additionally, the data is from 2021 and doesn’t reflect the impact of recent programs like the Affordable Connectivity Program, which began in 2022.

As we move forward, these findings underscore the need for more nuanced, data-driven approaches to addressing the digital divide. Policymakers and program designers should consider incorporating measures of internet quality and speed, not just binary access, into their equity assessments. They should also be prepared to adapt their strategies as the digital landscape evolves and new divides emerge.

Moreover, these researches opens up new avenues for investigation. Future studies could delve into the reasons behind these unexpected speed disparities, perhaps through qualitative research into internet usage patterns across different demographic groups. There’s also a need to explore how these speed differences translate into real-world outcomes in areas like education, employment, and health.

In conclusion, while this study doesn’t negate the very real challenges that minority communities face in terms of overall internet adoption, it does complicate our understanding of the digital divide. As we invest billions of dollars in expanding broadband access and promoting digital equity, we must ensure our efforts are guided by current, granular data rather than outdated assumptions. Only then can we hope to create a truly inclusive digital future for all Americans.

References:

- Theoretical perspectives on digital divide and ICT access: comparative study of rural communities in Africa and the United States

- An unexpected digital divide? A look at internet speeds and socioeconomic groups

- Bridging the digital divide

- Spatiotemporal investigation of the digital divide, the case study of Iranian Provinces