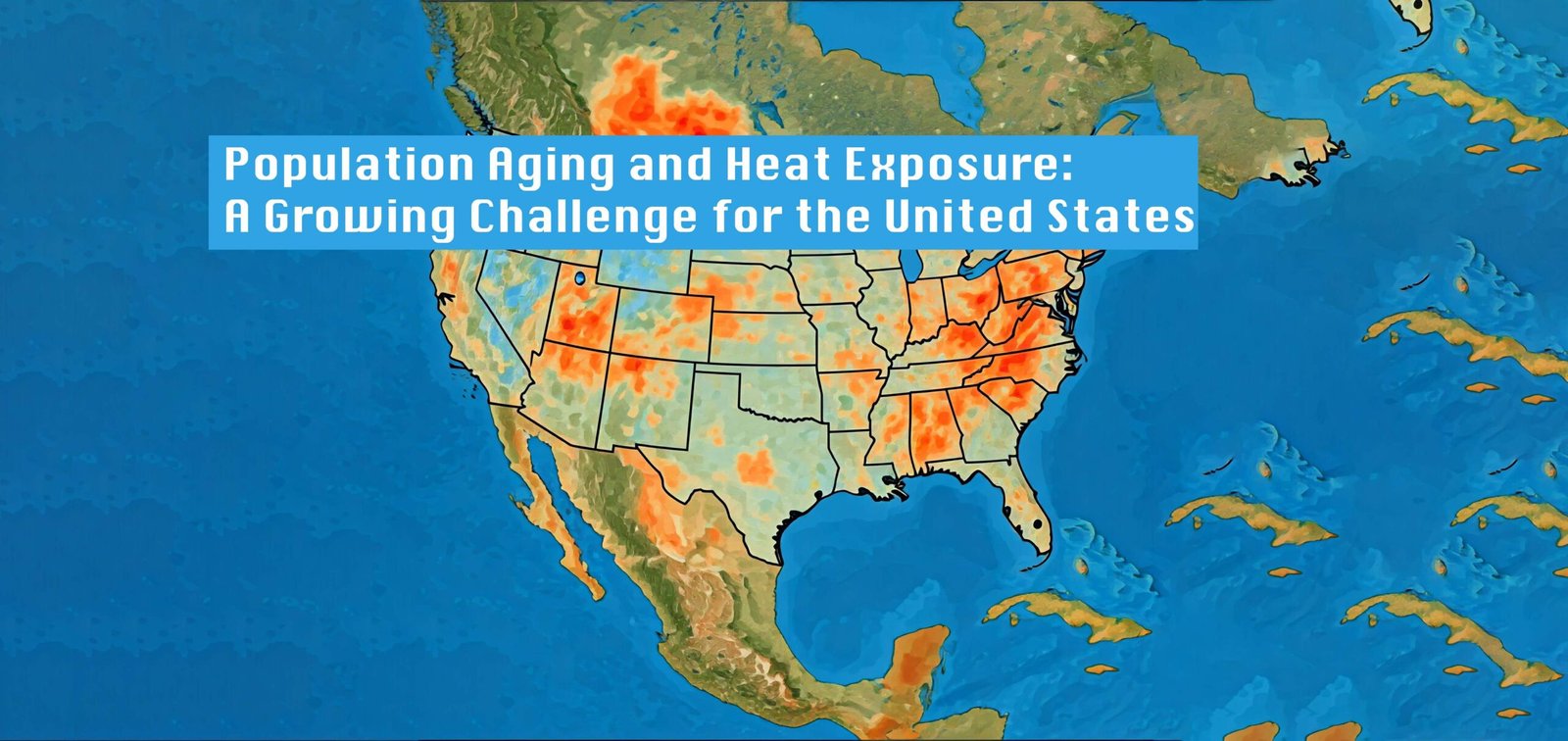

As the United States faces the dual challenges of climate change and an aging population, new research highlights how these trends are converging to create “hotspots” of vulnerability across the country. A recent study published in The Gerontologist journal provides the first comprehensive look at how rising temperatures and changing demographics will impact older Americans in different regions through the mid-21st century. The findings reveal a complex picture, with some areas facing steep increases in both heat exposure and the proportion of older residents, while other regions confront different combinations of climate and demographic shifts.

Study by Researchers:

Studies, conducted by researchers from several U.S. universities, analyzed county-level projections of population aging and climate change impacts through 2050. Using advanced climate models and demographic projections, the researchers mapped out where concentrations of older adults (defined as those 69 and older) are likely to intersect with increasing heat exposure.

Reasons for the Population Aging in USA:

Overall aging and warming trends: The proportion of Americans aged 69+ is projected to increase from 11% currently to around 17% by 2050. Meanwhile, a key measure of heat exposure – cooling degree days (CDDs) – is expected to rise by 52-73% nationwide by mid-century.

Regional variations: The impacts will not be uniform across the country. Many northern regions that currently have older populations but milder summers are projected to see dramatic increases in heat exposure. Meanwhile, some southern areas accustomed to extreme heat will experience more modest temperature increases but rapid growth in their older populations.

Emerging “hotspots”: Several regions stand out as particular areas of concern, facing high levels of both population aging and increasing heat:

- Coastal regions of Florida

- Parts of Texas, Oklahoma, and Arkansas

- Some rural areas in the Southwest

Urban challenges: Major metropolitan areas, especially in the Northeast and Midwest, may face steep increases in heat exposure coupled with aging infrastructure ill-equipped to handle temperature extremes.

Drivers of change: The relative impacts of climate change versus demographic shifts vary by region. Climate change is the largest driver of increasing heat exposure for older adults in historically cooler areas like New England and parts of the Midwest. In contrast, population aging is the bigger factor in many southern and western states.

Implications for Policy and Practice

Several study’s authors emphasize that different regions will require tailored approaches to protect vulnerable older adults from heat-related health risks. Some key recommendations include:

Education and early warning systems: In northern states and higher elevation areas unaccustomed to extreme heat, there’s a pressing need to educate older residents about heat risks and establish robust early warning systems for dangerous temperature spikes. However, the researchers note that heat alerts alone have not been shown to reduce mortality risks. Messaging needs to be carefully designed to overcome older adults’ tendency to underestimate their personal vulnerability to heat.

Infrastructure investments: Southern regions generally have more experience dealing with extreme heat, but will face mounting pressure on health care systems, utilities, and public services as their older populations grow. Expanding cooling centers, improving access to air conditioning, and upgrading power grids to handle peak demand will be crucial.

Targeted interventions: The study suggests leveraging the expertise of gerontology and geriatrics professionals to shape heat response strategies. This could include tailoring alert messaging for older adults, training home health workers to educate clients about heat risks, and using geographic information systems to help first responders locate vulnerable individuals during extreme events.

Balancing adaptation costs: While infrastructure upgrades like mandating backup power for long-term care facilities are important, policymakers need to carefully consider potential unintended consequences. High compliance costs could potentially divert resources from staffing or other aspects of care quality.

Regional cooperation: Given the uneven distribution of risks and resources, there may be a need for resource sharing or coordinated planning across state lines to protect vulnerable populations.

Challenges and Future Research Directions

Studies provide a crucial starting point for understanding the intersection of aging and climate change in the U.S., but the authors acknowledge several limitations and areas for future research:

Age groupings: Due to data constraints, the study used a relatively broad age category (69+). Future work should examine more specific age groups, especially the oldest-old (85+) who may be particularly vulnerable.

Additional risk factors: Beyond age and temperature, other demographic and geographic factors like income levels, urban vs. rural settings, and household composition could further refine understanding of vulnerability.

Urban heat islands: The study didn’t specifically account for the intensified heating effects often seen in urban areas due to built environments. This could be an important area for targeted research.

Adaptive capacity: While the study projects exposure levels, more work is needed to understand how different regions and populations might adapt to changing conditions over time.

Health impacts: This analysis focused on exposure levels rather than specific health outcomes. Connecting these projections to epidemiological data could provide more concrete estimates of potential health burdens.

Broader Implications

Beyond its specific findings, this research highlights the need for interdisciplinary approaches to major societal challenges. The convergence of demographic shifts and climate change creates complex, interconnected risks that require expertise from fields including gerontology, climatology, public health, urban planning, and public policy.

The study also underscores how geographic disparities in both climate impacts and population aging could exacerbate existing inequalities across the U.S. Regions facing the greatest combined risks often overlap with areas that have fewer resources to adapt, potentially creating compounding disadvantages.

From a theoretical perspective, the researchers suggest their findings support an expansion of “cumulative disadvantage” models in gerontology. While these frameworks typically focus on how individual-level factors accumulate over the life course to affect well-being in old age, this work demonstrates how disadvantages can also accumulate at population and regional levels through the interaction of demographic and environmental trends.

As both climate change and population aging accelerate in the coming decades, protecting vulnerable older adults from heat-related health risks will become an increasingly urgent priority across the United States. This study provides a valuable roadmap, highlighting where and how these dual trends are likely to intersect most dramatically.

The research makes clear that there is no one-size-fits-all solution. Different regions will need to tailor their approaches based on their specific combination of demographic shifts, changing temperature patterns, existing infrastructure, and resources. Proactive, evidence-based planning will be essential to ensure that communities can protect their growing older populations in a warming world.While the challenges outlined in this study are daunting, they also present opportunities for innovation in urban design, health care delivery, social services, and community resilience. By understanding these evolving risks now, policymakers, health professionals, and communities have a chance to get ahead of the curve and develop robust, age-friendly climate adaptation strategies for the decades to come.

Online reading list that expands on the topics covered in the study and article:

“Climate Change and Health: Older Americans” – U.S. Environmental Protection Agency

https://www.epa.gov/climate-indicators/climate-change-indicators-heat-related-deaths

“Heat and Health Tracker” – Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

https://ephtracking.cdc.gov/Applications/heatTracker/

“Climate Change and Older Americans: State of the Science” – American Journal of Public Health

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3945584/

“An Aging World: 2020” – U.S. Census Bureau International Population Reports

https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2020/demo/p95-20-1.html

“Fourth National Climate Assessment” – U.S. Global Change Research Program

https://nca2018.globalchange.gov/

“Heat Waves and Climate Change” – Center for Climate and Energy Solutions

https://www.c2es.org/content/heat-waves-and-climate-change/

“Climate Change and Extreme Heat: What You Can Do to Prepare” – EPA & CDC

https://www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2016-10/documents/extreme-heat-guidebook.pdf

“The Effects of Climate Change on the Health of Older People” – The Lancet

https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanplh/article/PIIS2542-5196(21)00082-4/fulltext

“Projections of Future Heat Stress in the United States” – Earth’s Future

https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1029/2020EF001886

“Climate Change and Health: Preparing for the Future” – National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences

https://www.niehs.nih.gov/research/programs/geh/climatechange/index.cfm

These resources provide a mix of scientific research, government reports, and public health guidance related to climate change, aging populations, and heat-related health risks. They can offer readers a deeper understanding of the issues discussed in the article.